Games Workshop

- Siem te Hennepe

- Apr 4, 2025

- 24 min read

Updated: Nov 17, 2025

What makes a company truly unique? Is it the product, the business model, or the way it captures its customers? Games Workshop might just be one of the most fascinating case studies in all three.

Describing Games Workshop simply as a creator and seller of plastic miniatures would be an understatement. It sells a world, a feeling, a sense of belonging, one that fans dedicate years on. It allows Games Workshop to ask a big premium on its products, just like LEGO. But does that translate into a great investment?

In this special episode, we sat down with Sonny from Secret Sauce Investing on Substack, who has owned Games Workshop since 2021 and knows the company inside and out. He helped us analyze and figure out makes Games Workshop so profitable, resilient, and yet risky at the same time.

If you want to understand how a niche company has realized a 16% CAGR on its stock price since 1995, hit play and find out!

Listen on Spotify:

Listen on YouTube:

Written Analysis - Games Workshop

For those who prefer the written word:

Audio analysis - Games Workshop

Listen on Buzzsprout:

Summary

Games Workshop’s massive pricing power comes from its unique positioning in the miniature (war)gaming niche, where it has no true competitors. Unlike board games or collectible card games, Warhammer requires significant time, money, and effort from players, making it unlikely to switch to another game. Once a player has built an army, learned the rules, and engaged in the community, they are deeply invested, both financially and emotionally. This level of customer lock-in allows Games Workshop to continuously raise prices while maintaining demand, a rare advantage in any industry.

Games Workshop must keep players happy and engaged, while also innovating, expanding, and maintaining product quality, all while raising prices without alienating players. No easy task. The fan base is passionate but also highly vocal, meaning any misstep, whether it’s a steep price increase, a poorly received game update, or a lack of engagement with the community, can lead to backlash. At the same time, the company must ensure strong margins and revenue growth for investors, which makes pricing decisions a constant tightrope walk. Striking the right balance between profitability and player satisfaction is one of the biggest risks to long-term success.

What makes Games Workshop a such a strong company, is its vertically integrated business model. It owns its entire supply chain, meaning it manufactures them, distributes them, and sells them directly through its own stores, website and 3rd-party sellers. This DTC model eliminates middlemen, keeping margins exceptionally high. Additionally, its intellectual property (IP) licensing, particularly in video games and potential TV adaptations, is pure profit with almost no costs.

Chapter 1 - Introduction

Games Workshop was founded in 1975 in London by Steve Jackson, John Peake, and Ian Livingstone. Initially, it started as a small-scale mail-order business for board games and tabletop RPGs, run from a bedroom. Over time, it evolved into the world's leading manufacturer of fantasy miniatures, known for its iconic Warhammer brand. Today, Games Workshop designs, manufactures, and sells its miniatures globally, operating through a vertically integrated business model that includes in-house production, dedicated retail stores, an online marketplace, and licensing agreements.

At its core, Games Workshop has built an entire ecosystem around its intellectual property (IP). Its flagship franchises, Warhammer 40.000 and Warhammer Age of Sigmar, are set in fictional universes that extend beyond physical miniatures into books, digital games, TV series, and even animated content.

1.1 - History

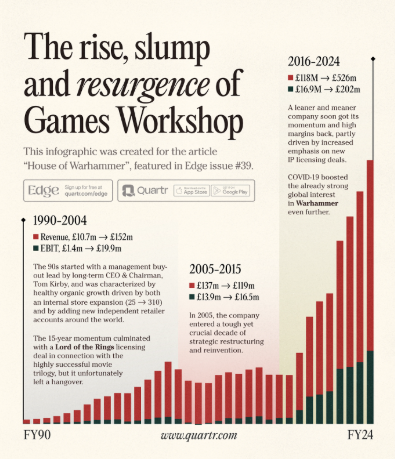

There are a few key moments in the history of Games Workshop that we will expand on. Since its IPO on the London Stock Exchange in 1994, Games Workshop has gone through three distinct phases, each with its own narrative, shaping the company's evolution and financial trajectory.

Phase 1 (1975-1985): From RPG distributor to a miniatures company

1978 – Opens its first retail store in Hammersmith, London.

1983 – Launches Warhammer Fantasy Battle, creating its own intellectual property (IP).

Phase 2 (1985-1995): Expansion and Warhammer 40.000

1987 – Introduces Warhammer 40.000, which becomes its most successful franchise.

1991 – Acquires Citadel Miniatures, fully integrating miniatures production.

1994 – Goes public on the London Stock Exchange.

Phase 3 (1995-2015): The struggles and reinvention

2000s – Faces flat lining revenues, struggling to modernize its business.

2015 – Kevin Rountree becomes CEO and leads a successful turnaround.

2017 – Warhammer’s fan base explodes online, leading to a massive share price increase from £5 to over £120.

Phase 4 (2016-Present): The licensing era

2021 – Launches Warhammer+, a subscription-based digital platform.

2023 – Announces a major Amazon deal to produce a Warhammer 40K TV series.

2024 – Reports record-breaking revenue and profits, reaching over £525 million in revenue.

Its history shows that Games Workshop’s strength does not ‘just’ come from making miniatures, it comes from owning and expanding IP that fans are deeply invested in. While many businesses struggle to create a loyal customer base, Games Workshop has turned its customers into a dedicated, passionate army of evangelists.

Chapter 2 - The Company

2.1 - The business model

At its core, Games Workshop (from now on GAW) is a vertically integrated business, meaning it controls every aspect of its production, from design and manufacturing to sales and distribution. Unlike many other toy and hobby companies that rely on third-party manufacturers and retailers, Games Workshop does everything in-house, giving it tight control over quality, pricing, and margins.

The company's primary revenue streams come from:

Figure 2 | Revenue distribution | TDI Visual

Trade: Bulk, wholesale transactions with third-party retailers or distributors.

Retail: Direct sales from company-operated stores where the end consumer purchases the product.

Online: Sales through the company’s own digital platform.

Licensing: Revenue from agreements that allow others to use the company’s intellectual property.

GAW had 548 stores at the moment of writing (Feb. 23rd) and expects to open 28 new stores in 2025. 75% of the stores are single-staff stores, meaning just a single employee/manager.

The goal is not necessarily to sell anything in the store itself, but to introduce people to the game, let them make their own character for free, guide them, offer support and answer any questions people have. The goal is to build an intimate relationship, between the brand, game, customer and community. We’ll explain later why this is so important. According to GAW’s 10K, every store is profitable. If not, they’ll relocate or close it. If we divide retail revenue (£118.9m) by the number of stores (548), the average store earns £217.000 in revenue annually.

2.2 - Culture

If you want to understand what makes Games Workshop (LSE: GAW) one of the most successful niche companies in the world, you need to look beyond its financials. Games Workshop (GAW) is not just another toy or gaming company. It is a community-driven, business with a monopoly-like hold over the miniature wargaming market. Games Workshop benefits from an engaged customer base that continuously reinvests in their collections. The business operates on a lifetime value model, where customers often start small but become increasingly valuable over time.

Games Workshop’s management philosophy is refreshingly simple. Unlike many corporations that focus more on the short-term, Games Workshop takes a long-term view in everything it does. CEO Kevin Rountree has made it clear:

The company hires employees who are fans of its games, ensuring that its workforce is not just skilled but deeply invested in the product. Many of GAW’s employees started as customers before joining the company, meaning they bring intrinsic passion into their work. For an investor, this kind of cultural alignment is a blessing. It means the company doesn’t have to work hard to convince its employees to care. They already do. This results (in theory) in higher employee retention, better customer service, and a more authentic brand presence. Games Workshop hires based on passion for the hobby rather than just experience or degrees. They believe that skills can be taught, but passion and alignment with company values cannot. According to their leadership:

GAW’s culture is not just internal, it extends to its customer base. Warhammer is more than a product; it’s a hobby. Customers spend hours assembling, painting, and strategizing. This level of engagement is rare in consumer products, making GAW’s customer base more of a devoted fandom than just buyers.

GAW’s management structure is also quite unique. It operates with a flat hierarchy, where decision-making authority is centralized in Nottingham but carried out with a high degree of autonomy. The company promotes from within, ensuring that new leaders deeply understand the business and its culture before stepping into senior roles.

Chapter 3 - Sector & Industry

3.1 - The tabletop gaming market

Miniature (war)gaming is a niche within the tabletop gaming market. It sits at the intersection of hobbyist culture, intellectual property (IP)-driven storytelling, and strategic gaming. The industry has witnessed sustained growth due to increasing engagement with tabletop games, expanding global communities, and the crossover appeal of franchises into digital entertainment and collectibles.

In 2024, the market was valued at approximately $15-20 billion and is projected to reach $34 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of roughly 10%. While large competitors like Hasbro and Mattel hold significant market shares, the industry is becoming increasingly fragmented due to the emergence of smaller vendors offering creative designs and family-oriented games.

In a world dominated by screens, people are craving real, face-to-face interactions more and more. It looks like board games are stepping up to fill that gap. Whether it’s families gathering around classic strategy games, friends diving into co-op adventures, or hobbyists spending hours painting intricate miniatures, the demand for tabletop experiences is growing. This is a tailwind for companies like Games Workshop. However, Gen Z and Gen X seem to prefer online games more.

At the same time, the industry isn’t stuck in the past. Many of the biggest franchises: Dungeons & Dragons, Warhammer, Magic: The Gathering, have successfully expanded into video games, mobile apps, and digital board game adaptations, pulling in new audiences. And let’s not forget the power of nostalgia, games that were childhood staples for millennials are now being rediscovered as they introduce their own kids (or just relive the magic themselves). The result is a ‘boring’ yet growing market.

3.2 - Competitors

The tabletop gaming industry is a mix of established names and newcomers, each bringing something different to the ‘table’ (sorry, bad word play). Big names like Hasbro, Mattel, and Games Workshop dominate thanks to their strong brand recognition, extensive distribution networks, and valuable licensing deals with franchises like Star Wars and Marvel. Unlike mass-market board games (think Monopoly, Risk or cards) that rely on low-cost, high-volume sales, companies in the miniature wargaming and trading card game (TCG) segments operate on premium pricing and DTC models. Games Workshop, for example, enjoys industry-leading margins, thanks to its loyal Warhammer community and simplicity of the products.

One major trend reshaping the industry is digital expansion. Whether it’s Magic: The Gathering Arena, Dungeons & Dragons Beyond, or board game adaptations on Steam and mobile platforms, the biggest players are finding ways to merge tabletop and digital gaming. While this helps reach new audiences, it also introduces competition, especially from video games, mobile apps, and online RPGs. Companies that can balance traditional gameplay with modern digital strategies will be best positioned for future success.

Some other interesting statistics I found:

Over 20.000 board game publishers are known to exist around the world as of 2020.

Of these, Asmodee accounts for 18% of the global board games market share (1st), Hastro 12% (2nd) and Ravensburger 4% (3rd). Asmodee owns games like Ticket to Ride, Catan, Exploding Kittens, etc. Hasbro owns games like Monopoly, Cluedo and Jenga. Ravensburger owns games like Disney Villainous, Labyrinth, The Castles of Burgundy, and Scotland Yard.

As of 2024, more than 150,000 board games and related titles are listed on BoardGameGeek, a well recognized online database and forum.

By 2026, the strategy and war games segment is anticipated to hold a 67% share of global board games revenue.

Chapter 4 - Competitive advantages

Warhammer players don’t just buy a game, play it a few times, and move on. They invest hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars into building, painting, and playing with their armies. This level of commitment creates a high barrier to entry for competitors. Once someone is deep into the Warhammer ecosystem, switching to another game isn’t just about buying new miniatures, it means leaving behind a community, a collection, and a personal investment that spans years.

Games Workshop operates in a highly specialized niche where no competitor matches its scale, brand loyalty, or ecosystem. While other miniature wargames exist, none have built the same dedicated player base, deep lore, or global retail presence. Companies like Privateer Press (Warmachine), Warlord Games (Bolt Action), and Corvus Belli (Infinity) offer alternatives but lack Games Workshop’s frequent releases, IP ownership, and mass-market appeal. Some, like Atomic Mass Games (Star Wars: Legion, Marvel: Crisis Protocol), rely on licensed properties, limiting their control over long-term growth. Others, like Mantic Games (Kings of War, Deadzone), position themselves as cheaper alternatives but struggle to compete with Warhammer’s premium branding and deep engagement.

The company also owns its entire supply chain, from design to manufacturing to retail. This means GAW doesn’t rely on third-party suppliers as much as other companies, keeping costs down and profit margins high.

Intangible assets

Its intangible assets come down to 3 things: 1) its brand, 2) its IP and 3) community. Warhammer is an entire fictional universe that’s been expanding for over 50 years. The depth of the Warhammer lore and world-building is one of GAW’s strongest competitive advantages. In fact, many people who aren’t familiar with the hobby still associate miniatures with Warhammer by default. This level of brand recognition is extremely difficult for competitors to replicate.

Beyond miniatures, GAW has successfully expanded its intellectual property (IP) into other areas, through video games, books, and licensing deals. See some examples below.

Part of the intangible assets that make their moat so strong and durable comes down to its loyal community. Warhammer is more than just a (board) game, it’s a social experience. People paint miniatures together, play in tournaments, discuss strategies online, and engage with Warhammer lore through books and videos. This level of engagement keeps players actively involved even when they’re not buying new miniatures. It also means that once someone is part of the Warhammer community, they’re unlikely to leave, creating high customer retention and long-term revenue stability. It also allows for premium pricing, which we will see later in their financials.

The company also actively supports this community. Warhammer stores aren’t just retail spaces, trying to sell items. The stores are meant to be ‘hubs’ where new players are introduced to the hobby and veteran players come to compete and connect. The Warhammer Community website, YouTube channel, and subscription service (Warhammer+) further reinforce this engagement.

Overall, Games Workshop has built a business that is extremely difficult to disrupt. Its combination of strong branding, deep customer investment, vertical integration, IP licensing, and a dedicated community creates a formidable competitive advantage that will be hard to disrupt. The obvious risk here is that they are dependent entirely on a single game.

Chapter 5 - Management

Games Workshop’s management team is a blend of long-tenured insiders who have been deeply involved in the company’s operations for decades.

Kevin Rountree – CEO

Kevin Rountree (CEO) has been with the company since 1998 (25+ years), rising through the finance and operations departments before taking the helm in 2015.

Since taking over, Rountree has steered Games Workshop to exceptional profitability, doubling down on its vertically integrated manufacturing model, international expansion, and licensing opportunities. His approach seems calculated and disciplined. The company avoids debt, keeps operations simple and lean, and prioritizes long-term sustainability over short-term publicity.

Before we continue, I want to share something from the FY14-15 annual report. As you know, we always look back in time to assess whether management is honest, delivers on its promises, remains consistent, and if there are any irregularities to uncover. Now, I came across this particular excerpt from a time when Games Workshop was facing tougher challenges, and I found it too good not to share. It was written by former CEO Tom Kirby.

“This year Kevin Rountree took over the day-to-day running of your company. I stayed on as non-executive chairman, so you still get this preamble.” [...]

“The Great Master Plan continues: cutting costs, becoming more efficient, providing excellent returns on capital and paying dividends. We do not set out to pay dividends, we set out to run an efficient company that uses money wisely. We know we are doing that well when we have more money than we need; this becomes your dividend.”

“One bit of the GMP (Great Master Plan) remains stubbornly unrealized – sales growth. We knew that the huge infrastructure changes we have been making these last few years (and are still making, we have just signed off on a new ERP system) would be disruptive, so we are not surprised that many trade accounts across Europe no longer trade with us. Nor are we surprised at the amount of work we have to do to get great managers in all our stores following the move to one-man operation. Our efforts, unfortunately, have coincided with truly dreadful trading conditions and, for the first time in our history, a year when the pound was strong against the euro and the dollar simultaneously.”

“Our natural hedge hasn’t been one this year. You can see the effects of our lack of sales growth in our gross margin, cost-savings in the maintenance of our net margin, and currency everywhere. Nevertheless, as I am sure he will tell you, Kevin has plans for sales growth across the board. More stores, growth in our existing stores, more trade accounts and a better performance from our mail order service.”

“I do not often talk about our products, partly because I think they speak eloquently for themselves, and partly because it is important for everyone to remember (that’s owners, customers and staff) we are a business. We need to be here next year if you want more of the exquisite models we make. To be here next year, we have to do what all our customers want, not just a noisy few, and find a way of making money doing it. This year, though, is an exceptional year. Not only have we just opened a wonderful new visitor centre on time and under budget (take a bow, Tony) we have also relaunched Warhammer. The visitor centre is a cathedral of miniatures with the world’s largest and most spectacular diorama. Only £7.50 and a day you will remember all your life.” [...]

“As I write, the world is tumbling in chaos around us. Pundits discover they cannot predict elections, the Americans ride to the rescue of world football (thank you, Uncle Sam), Sunderland escape relegation, again, the UK will split up into its consistent parts, it will leave Europe; and yet we struggle on. Babies get born, the rain falls the sun shines and the plants grow, our chickens keep laying, and Games Workshop still employs over 1500 people, supporting 1500 families all over the globe, making the best miniatures money can buy, providing one of the best investments in our owners' portfolios, and having a great deal of fun doing it.”

I loved finding this piece because it’s a rare example of corporate writing that actually feels human. It’s straightforward, self-aware, and deeply passionate, not just about running a profitable business, but about the hobby, the people behind it, and the long-term vision. There’s something very Buffett-like about the way Kirby writes (and so does Rountree by the way). They don’t sugarcoat the company’s struggles, they openly acknowledge missed sales growth, struggles, and operational challenges. Yet, instead of spinning it into corporate fluff, they keep it clear, practical, and solution-oriented. There’s no empty optimism, just conviction: a belief in what they do, a plan for improvement, and a recognition that the world continues to turn, no matter how chaotic things seem. That kind of clarity and long-term thinking is rare, and it’s precisely what makes Games Workshop so fascinating from an investor’s perspective.

Alright, I promise to keep the other members of management a bit more brief.

Liz Harrison – CFO

Appointed in 2024, has been part of the company since 2000 (also 25+ years). She previously led financial reporting and business analysis, ensuring continuity in Games Workshop’s cost-conscious approach. Interestingly, Harrison is known for her extreme privacy, there are no public images of her, and she avoids media appearances.

Unlike many modern businesses, Games Workshop does not rely on high-profile external hires. Instead, it promotes from within, reinforcing a company culture rooted in operational discipline, cost efficiency, and product quality. Management remains highly cost-conscious, refusing to spend on mass advertising or premium retail locations. While this ensures profitability, it also raises questions about the ceiling for organic growth in a market where competitors invest aggressively in digital marketing, influencer partnerships, and wider distribution channels.

5.1 - Incentives

Something I somewhat dislike are their incentives. The remuneration structure at Games Workshop consists of:

🟢Base salary

🟢Pension and benefits

🟢Exceptional Bonus Award. Up to 150% of base salary + mandatory share purchase requirement. 67% of any bonus must be used to buy shares and held for 3 years.

🔴There is no long-term incentive plan (LTIP).

🔴No long-term share awards (unusual for a FTSE 250-level company)

🔴Bonuses are entirely discretionary, rather than based on predefined performance targets (rare in public companies).

This structure has clear limits, but it also avoids (unnecessary) excessive management payouts. Most FTSE 250 and gaming-related companies have a structured LTIP with SBC-rewards over multiple years. Games Workshop’s absence of LTIPs makes it an outlier. They prioritize a stable base salary and flexible cash bonuses.

For comparison: Hasbro, Activision Blizzard, and Electronic Arts: Use LTIPs and SBC, to align management with shareholders. Games Workshop’s approach is simpler, and also avoids dilution. So it has its pros and cons.

In 2023/24, management received the maximum possible bonus (150% of salary) due to record growth in revenue and profit, alongside record dividends and profit-sharing for staff. Overall, I think the incentives are fine. Perhaps, they’re even good this way, since excessive bonuses or trying to please shareholders over loyal players, could hurt them long-term.

5.2 - Skin in the game

While there is a lot to like about the company, I dislike their skin in the game. Despite their long tenure, Rountree and Harrison own small stakes in Games Workshop, compared to large institutional investors such as Baillie Gifford (11.2%). This raises an important question, while management prioritizes financial conservatism and long-term growth, their direct financial alignment with shareholders is minimal.

The base salary of Kevin Rountree was £739.000 (after an increase of 7.4%).

The Base salary of Lizz Harrison was £390.000 (after an increase of 7.4%).

Kevin Rountree (CEO) owns 15.394 shares, worth £2.19 million, or almost 3 times his base salary. Liz Harrison (CFO) owns 3691 shares, worth £524.000, or just 1.3 times base salary. It’s not a red flag per se, but it’s not a lot if you ask me.

Chapter 6 - Financial analysis

6.1 - Key numbers

Revenue has grown from £119 million to £577.5 million (FY24-FY25) or 18% CAGR. The cost of goods sold has grown slightly slower, with 17% CAGR.

For a company with 500+ retail shops, selling mostly physical goods, a 71% gross margin is exceptional. The operating margin has also tripled, from a high 13% to almost 41%. This shows unbelievable loyalty and pricing power (in the past). It remains to be seen if they can sustain or grow margins.

Profit and free cash flow margin are very similar and have grown from 10% to 30% over the past decade. Unbelievable.

It shouldn’t be surprising now that profits have grown with a 32% CAGR over that same time period. Outpacing revenue significantly.

Shares outstanding has grown just 0.3% CAGR over the past decade. This is negligible. Financially, this company blows it out of the park.

The stock price (40.6% CAGR) has outgrown EPS (31.8% CAGR) significantly , so I assume the valuation will be higher than we’d like, but we’ll see about that in the valuation chapter. It also means investors have noticed the exceptional financial position, quality and have high expectations for the company.

6.2 - Capital allocation

Capital allocation is very straightforward. It’s basically repaying debt and dividends. They don’t do acquisitions or buy back shares.

6.3 - ROCE

Since Games Workshop’s capital structure is simple (no serious debt, few major investments), ROCE is the more practical and informative metric. ROIC is still useful, but because the company doesn’t do large-scale reinvestment projects or M&A, it won’t vary as much. But for evaluating its efficiency in generating shareholder returns and running its core business, ROCE is the better fit. In Games Workshop's case, they're remarkably similar. And yes, you’re seeing it right… They have an ROCE (and ROIC) of over 75%. Which is ridiculously high.

Games Workshop’s exceptionally high ROCE is possible because of its capital-light business model and strong pricing power. Unlike traditional manufacturers, it doesn't need to continuously invest in massive factories or expensive equipment to grow. Instead, its focus is on intellectual property (Warhammer 40K, Age of Sigmar), high-margin miniatures, and an engaged customer base that repeatedly buys new products. Since the company vertically integrates production (meaning it makes most of its own miniatures rather than outsourcing), it captures more of the profits. Combine this with minimal debt, disciplined cost control, and steady price increases, and the result is insane capital efficiency. The company also reinvests relatively little into expansion, distributing large dividends instead, which further inflates ROCE. Very impressive, and before starting the analysis, I wouldn’t have imagined anything close to this.

6.4 - Debt analysis

We can be very brief on debt. They have no long-term debt. All they have are long-term leases (soft debt). They have over three times as much cash than long-term leases. Financially they are extremely healthy.

6.5 - Compare with competitors

While it might seem like there should be plenty of competition, the reality is that no company fully replicates them. That said, if I had to pick 3 companies that could be considered competitors, i’d pick these:

Hasbro: The Gathering & Dungeons & Dragons

Privateer Press: Warmachine & Hordes

Reaper Miniatures: Various RPG Miniatures

While there are companies that sell miniatures, board games, or tabletop experiences, none of them compete directly with Games Workshop’s full ecosystem. It’s a bit like LEGO. Sure, there are cheaper LEGO alternatives, but LEGO fans stick with LEGO because of the ecosystem, quality, and nostalgia. Or Pokémon. People grew up with Pokémon, invested years into it, and aren’t going to start fresh with a knock off, just like Warhammer fans won’t dump their armies for a new miniatures game.

The biggest reason Games Workshop has no true competitors is its combination of storytelling and community-driven engagement. It's almost impossible to take away market share from them unless they mess up themselves, which we will talk about in chapter 7 - Risk analysis.

6.6 - KPI’s

If you want to track the performance of Games Workshop, these are the most important KPI’s to keep track of:

Revenue growth

Core operating profit

Licensing revenue

Number of own stores by territory

Number of ordering stockist accounts by territory

Customer engagement

Let’s go through them quickly.

Revenue growth

Revenue growth is the clearest indicator of whether Games Workshop is expanding its player base and selling more miniatures. Since Warhammer is a long-term hobby, revenue growth means new players are joining, and existing ones are spending more. If revenue starts slowing down, it could mean the hobby is reaching saturation, competitors are taking share, or pricing power is weakening.

Core operating profit

This measures how much money Games Workshop actually keeps after covering its costs (materials, staff, rent, etc.). Unlike revenue, which just tracks sales, operating profit shows if GAW is running efficiently. Since Game Workshops asks significant premiums on its products, profit margins should remain strong. If they start slipping, it could be a warning sign. Operating profit has grown over 32% CAGR over the past decade.

Licensing revenue

This is revenue GAW earns from licensing Warhammer IP to other companies (video games, books, TV shows, etc.).

It’s 100% profit because GAW doesn’t have to make or sell anything, it just collects fees. It’s low-effort, high-margin revenue.

Number of own stores by territory

Games Workshop sells directly through its own stores. More stores mean better global presence, more brand control, and more direct sales. If Games Workshop is opening more (profitable) stores, it suggests growth and strong demand. All stores must be profitable, or they’ll be closed.

The Games Workshop team has highlighted significant opportunities, including reaching 200 stores in North America soon. That would mean +28 new stores.

Number of ordering stockist accounts by territory

Stockists are third-party retailers that order and resell GAW products (local game stores, comic shops, etc.). If independent game stores keep restocking Warhammer, that’s a healthy sign. If they start dropping the product, it could mean Warhammer is getting too expensive or losing popularity.

Since sharing this as a KPI, their 3rd-party retailers channel has grown by a 10% CAGR. 3rd-party form the largest portion of revenue today (55%).

Customer engagement

This one is difficult to measure yourself, other than being deeply invested in their community or the game itself. You’ll have to trust management to be able to calculate or estimate this. Warhammer is a lifestyle hobby. The company thrives on community, storytelling, and long-term engagement from fans. If engagement rises, it suggests strong customer retention and word-of-mouth growth. If engagement drops, it could mean the brand is losing relevance, younger players aren’t interested, or community frustration is growing. GAW measures that through their own content channels, such as warhammer-community.com, reach and socials. I believe their subscription, Warhammer+, is also a good way of tracking engagement. Warhammer+ has been available since 2022 and has grown significantly. A subscription costs €55 a year or €6.50 a month.

2021-2022 (starting year): <100.000 subscribers

2022-2023: 136.000 subscribers (worth roughly €7.48 million annually)

2023-2024: 176.000 subscribers (worth roughly €9.68 million annually)

Chapter 7 - Risk analysis

7.1 - Risks

Like any business, Games Workshop isn’t without risks. There are several challenges that could hurt the businesses.

3D Printing and counterfeits

One of the biggest long-term risks for GAW is the rise of affordable 3D printing. High-quality plaster printers are becoming cheaper and more accessible, allowing players to create unofficial miniatures at a fraction of GAW’s prices. While official Warhammer miniatures maintain a higher standard of quality and durability, the potential for piracy remains a threat, especially for casual players who put cost over authenticity. Ask yourself, how likely would it be if you could make your own LEGO-set for €10 instead of €60?

Customer backlash

GAW has strong pricing power, but there’s a limit to how much players will tolerate. The company has consistently raised prices on miniatures, rulebooks, and accessories, leading to growing frustration within the community. After speaking with players and reading reviews, here are a few examples of complaints.

"GAW's prices are absurd, and their 'woe as me' reasoning for raising prices every 6-12 months is even more absurd considering they continue to post record profits year after year." - Warhammer player for 10+ years

"The regional pricing alone absolutely kills me. Kits are 30%+ more in the US, and a price hike every 6 months is only making it worse." - Warhammer player for 5 years

Dedicated Warhammer fans continue to pay, but repeated price hikes could push more casual players toward cheaper alternatives or secondhand markets. If the company overestimates demand elasticity, it risks alienating parts of its customer base. This is a real balancing act between creating shareholder value (increasing volume and prices) and keeping customers pleased.

GAW’s intellectual property (IP) is one of its strongest assets, but protecting it is a constant battle.

7.2 - Opportunities

Expansion into digital

GAW has only just begun to tap into the full potential of its IP. The upcoming Amazon Prime Warhammer 40K series, along with ongoing video game releases, could significantly boost Warhammer’s mainstream visibility. If successful, this could drive new players into the hobby** and open doors for additional TV, movie, and digital content deals. Here’s what CEO Rountree said about its IP (although a bit biased, he’s also a lot more experienced).

We own what we believe is some of the best underexploited intellectual property (‘IP’) globally. [..] A few notable games were launched including Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine 2 and Warhammer 40,000: Speed Freeks. [...] We concluded our negotiations with Amazon [...] for the adaption of Games Workshop's Warhammer 40,000 universe into films and television series, together with associated merchandising rights. - CEO Games Workshop FY24

This indicates that they are increasingly focusing on digital growth, but only under their terms. They are very strict when it comes to this particular topic. They don't want their name to be hurt because it's all they have.

International growth

GAW has strong sales in the UK, US, and Europe (close to 90%), but it has room to expand elsewhere (Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East). Markets like China and Japan have growing tabletop gaming communities, and GAW is actively working on expanding its retail and distribution footprint in these regions.

Expanding beyond

While GAW is known mostly for its miniature wargaming, there is potential for more casual and entry-level products. Board games, card games, and simplified tabletop experiences could attract new audiences without requiring the full commitment of traditional Warhammer. Even though this might hurt margins, it does allow more potential fans to spend more later. This approach has worked well for competitors like Magic: The Gathering and Dungeons & Dragons, which have expanded beyond their core fan bases.

Chapter 8 - Valuation

8.1 - Ratio's

Since there aren’t any true competitors that can be directly compared to Games Workshop, we will primarily assess its valuation based on its historical performance.

Games Workshop has consistently high operating and net profit margins, meaning earnings accurately reflect its business strength. In that case, P/E is actually useful. Based on the figure below, it’s somewhere in between. People recognize its quality, and it’s not as cheap as before 2020, but it’s also not as expensive as it was during Covid-19. (Mostly due to depressed earnings).

8.2 - Scenario analysis

Games Workshop has managed to reach 30%+ margins already and based on their moat, pricing power and future, I think this should stay stable or grow a tiny bit more.

Revenue growth is a bit more tricky, since GAW doesn’t give any outlook. Revenue growth is based on industry average (approx. 10%) and analyst expectations (3-10%). And then, to be conservative, dropping it every 3 years.

A 7-8% annual return is not a lot, especially considering my assumptions. For me personally, the risk-reward is not attractive at today's price (£145).

Chapter 9 - Conclusion

Games Workshop is a remarkably strong business. It has a simple yet highly profitable model, extremely loyal customers, and unmatched pricing power. The company operates in a niche with high barriers to entry, virtually no direct competition, and a dedicated fan base that is both financially and emotionally invested.

Financially, it is one of the most profitable companies in its space. With zero debt, an astonishing return on capital employed of over 75%, and profit margins exceeding 30%, its capital efficiency is outstanding. The company benefits from vertical integration, controlling everything from production to sales, which keeps costs low and profits high.

Despite these strengths, there are risks that make it less attractive as an investment at today’s price. While its loyal customer base provides stability, the company faces an ongoing challenge in maintaining a delicate balance between profitability and customer satisfaction. Raising prices helps margins but risks alienating players. Another concern is management’s relatively low ownership in the company. While the leadership team has been in place for years and has executed well, their direct financial alignment with shareholders is limited. Also, the stock seems fully valued, leaving little margin of safety.

Although there is far more to like than to dislike about Games Workshop, I will not be adding it to the TDI watchlist. The key reason is that I don’t believe I have a real edge with this company. I lack the deep, firsthand understanding of Warhammer’s long-term durability, the emotional investment of its fan base, and the nuanced insight needed to judge whether the game is making the right strategic moves for all involved parties. Without that conviction, I can't confidently assess the company's future trajectory, making it a pass for me.