LVMH

- Siem te Hennepe

- May 30, 2025

- 35 min read

Updated: Nov 17, 2025

As many of our loyal TDI members know by now, I’ve got a soft spot for luxury businesses. Not necessarily because of the value they add to society (that’s up for debate), but more for what goes on behind the scenes: the psychology, the anti-marketing principles, the rich history, and all the intricate layers that make these companies so fascinating. In this analysis, we dive into the biggest, and arguably most iconic, luxury company in the world. Or rather, luxury holding, if we're being precise.

By the end of this analysis, you’ll have a deep understanding of how LVMH transformed the luxury industry, its strategic approach to acquisitions, and how it maintains its position as one of the leaders in luxury goods.

Audio analysis - LVMH

🎧 Listen on Buzzsprout:

🎧 Listen on Spotify:

Listen on Buzzsprout or listen offline:

🎁 Bonus content

Written Analysis - LVMH

For those who prefer PDF:

Summary

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton is the world’s largest luxury conglomerate, home to over 75 iconic brands across six segments including Fashion & Leather Goods, Wines & Spirits, and Perfumes & Cosmetics. Its most valuable division, Fashion & Leather Goods, led by Louis Vuitton and Dior, delivers industry-leading margins and accounts for the bulk of profits.

The group’s strength lies in its decentralized model: each brand retains creative independence, while leveraging LVMH’s global infrastructure. This structure, combined with strong pricing power, allows for resilience across cycles. Bernard Arnault and his family maintain tight control (64% voting rights), with a clear succession path unfolding among his five children.

Valuation-wise, LVMH trades at an attractive ~30% discount to intrinsic value based on a sum-of-the-parts analysis. For long-term investors, an additional ~18% discount is available through Christian Dior SE, the holding company that owns 42% of LVMH.

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1 - Why analyze LVMH?!

As many of our loyal TDI members know by now, I’ve got a soft spot for luxury businesses. Not necessarily because of the value they add to society (that’s up for debate), but more for what goes on behind the scenes: the psychology, the anti-marketing principles, the rich history, and all the intricate layers that make these companies so fascinating. In this analysis, we dive into the biggest, and arguably most iconic, luxury company in the world. Or rather, luxury holding, if we're being precise.

I want exposure to a luxury name in my portfolio because of the pricing power, resilience during tough economic times, customer loyalty and their long-term strategic vision. This can reward shareholders if done right. Luxury companies don’t chase quarterly profits, but rather build with the upcoming decades in mind. That’s exactly the kind of mindset I want to align with as a shareholder.

Also, as you might know (or not), I sold my stake in Kering for several reasons I won’t go into here. But if you’re going to own just one luxury name, you better make sure you’re getting the best value for money. I’ll be the first to admit Hermès, Ferrari, or even Brunello Cucinelli might outclass LVMH in terms of pure luxury. However, one could argue that LVMH is a lot more resilient and diversified long-term. For that reason, I want to go deeper than ever before into LVMH to decide whether I should sell it, double down and make it a cornerstone, or just keep it as-is. That means checking my biases at the door and staying brutally honest.

Let’s start with a brief introduction.

LVMH was officially established in 1987, but it came about through a unique and strategic merger. Louis Vuitton, the iconic fashion brand, and Moët Hennessy, the leading champagne and spirits producer, combined forces under the visionary leadership of Bernard Arnault. Since its inception, LVMH has grown into the largest luxury goods conglomerate in the world. The company is involved in a broad range of luxury sectors, from fashion and leather goods (think Louis Vuitton and Fendi), to wine and spirits (Moët & Chandon, Hennessy), cosmetics (Sephora), and even fine jewelry (Tiffany, Bulgari).

By the end of this analysis, you’ll have a deep understanding of how LVMH transformed the luxury industry, its strategic approach to acquisitions, and how it maintains its position as one of the leaders in luxury goods.

Enjoy.

1.2 - History

The history of LVMH is closely tied to Bernard Arnault, the chairman and CEO, who has led the company since the 1980s. Arnault grew up in northern France and came from a wealthy but non-luxury family. His career began in the family construction business, but he later shifted his focus to real estate and textiles. His interest in luxury brands, particularly Dior, started when he realized the untapped potential of underperforming but prestigious brands.

The big turning point came in the early 1980s when Arnault acquired Christian Dior, a brand that was struggling at the time. Arnault believed that Dior, under the right leadership, could be turned around, and he was right. This acquisition marked the beginning of LVMH’s expansion. Arnault’s vision was clear, luxury brands, while rich in heritage, often lacked the management expertise to reach their full potential. By acquiring them and taking full control over their distribution, marketing, and production, Arnault set LVMH on its path to dominance.

The merger between Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy in 1987 was a pivotal moment. It was a strategic move to form a group that could withstand external pressures, like potential takeovers. This move helped LVMH grow stronger and laid the groundwork for further acquisitions in the years to come. It was about taking businesses that were underperforming or not fully optimized and turning them into world-leading names. Over the years, Arnault has acquired many other well-known brands, such as Bulgari and Tiffany, expanding LVMH’s reach in various luxury markets, from jewelry to fashion.

Now, the history has been told by so many names, that it doesn’t add anything to this analysis. Here are some great sources on the history of LVMH, Arnault and Dior if you want to know more:

Acquired - LVMH

Business breakdowns - The wolf in cashmeres conglomerate

Here are the key moments in LVMH's history:

1987: The merger of Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy established LVMH.

1988: Acquisition of Givenchy, a brand known for its timeless style, famously associated with Audrey Hepburn. This acquisition set the stage for LVMH’s luxury fashion empire.

1990s: LVMH began acquiring other prestigious brands, like Givenchy, Fendi, and Marc Jacobs, which helped expand its presence in fashion.

1992: Creation of an Environmental Division. Following the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, LVMH created a division focused on the environment, becoming one of the first luxury groups to do so. This underscores LVMH's commitment to sustainability.

1993: Acquisition of Kenzo and Berluti. Kenzo, founded by designer Kenzo Takada, is acquired by LVMH, infusing the group with its unique "Jungle" style. Berluti, a renowned Italian brand, joins the group, bringing its bold and classic design expertise.

1994: Acquisition of Guerlain. Guerlain, one of France’s most prestigious perfume houses, joins LVMH, expanding its footprint in the fragrance market with a legacy of timeless elegance.

1997: Acquisition of Sephora and DFS. LVMH acquires Sephora, revolutionizing the beauty and cosmetics industry by offering a wide range of products and personalized services. DFS, a luxury travel retailer, also becomes part of the LVMH family.

1999: Creation of the Watches & Jewelry Division. LVMH establishes its Watches & Jewelry division, further diversifying into high-end timepieces with the acquisition of TAG Heuer, marking a major expansion in this luxury sector.

2001: Acquisition of Fendi. Fendi, known for its craftsmanship and Roman roots, joins LVMH, reinforcing its leather goods and fashion portfolio.

2007: Acquisition of Groupe Les Echos. LVMH acquires Les Echos, a leading French financial news outlet, marking the Group’s expansion into media.

2011: The acquisition of Bulgari marked LVMH’s first major move into the jewelry market.

2019: LVMH acquires Tiffany & Co., one of the most renowned jewelry brands in the world, further solidifying its leadership in the luxury jewelry market.

2024: LVMH, Premium Partner of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games. LVMH becomes a key partner in the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

2025: LVMH announces a 10-year partnership with Formula 1.

Chapter 2 - The Company

2.1 - The business model

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton is a luxury goods conglomerate (or holding) that makes money by owning and managing a collection of high-end brands across various sectors. The company operates a portfolio of over 75 brands (also known as Maisons), including some of the most prestigious names in luxury. Each brand has its own distinct identity but benefits from the scale and financial backing of LVMH. The 75 Maisons are organized into six business groups, based on the age of the founding of the brand.

14th century: 16th century:

1365: Le Clos Des Lambrays 1593: Château D’yquem

18th century: 19th century:

1729: Ruinart 1803: Officine Universelle Buly

1765: Moët & Chandon 1815: Ardbeg

1777: Hennessy 1817: Cova

1772: Veuve Clicquot 1828: Guerlain

1780: Chaumet 1832: Château Chevalblanc

1837: Tiffany & Co.

20th century: 1839: L’épée 1839

1908: Les Echos 1843: Krug

1914: Patou 1843: Glenmorangie

1916: Acqua di Parma 1846: Loewe

1923: La Grande Épicerie de Paris 1849: Royal van Lent

1924: Loro Piana 1852: Le Bon Marché

1924: Chez L’ami Louis 1854: Louis Vuitton

1925: Fendi 1858: Mercier

1936: Dom Pérignon 1860: Tag Heuer

1936: Minuty 1860: Jardin D’acclimatation

1944: Le Parisien-Aujourdi’hui en France 1865: Zenith

1945: Celine 1870: La Samaritaine

1945: Christian Dior Couture 1894: Bvlgari

1947: Parfums Christian Dior 1895: Berluti

1947: Emilio Pucci 1898: Rimowa

1949: Paris Match

1952: Givenchy

21st century:

1952: Consaissance des arts 2006: Maisons Cheval Blanc

1955: Chateau Galoupet 2006: Château D’esclans

1957: Repossi 2006: Armand de Brignac

1957: Vuarnet 2007: Barton Perreira

1959: Chandon 2008: KVD Vegan Beauty

1960: DFS 2009: Maison Francis Kurkbdjian

1969: Sephora 2010: Woodinville

1970: Kenzo 2013: AO Yun

1972: Perfumes Loewe 2016: Cha Ling

1973: Joseph Phelps 2017: Fenty Beauty by Rihanna

1974: Investir-Le Journal des Finances 2017: Volcán de mi Tierra

1976: Belmond 2020: Eminente

1976: Benefit Cosmetics 2024: Sirdavis

1980: Hublot

1983: Ole Henriksen

1983: Radio Classique

1984: Marc Jabocs

1984: Make up for ever

1985: Cloudy Bay

1988: Kenzo Parfums

1991: Fresh

1992: Colgin Cellars

1993: Belvedere

1996: Terrazas de los Andes

1998: Bodega Numanthia

1999: Cheval des Andes

The company generates its revenue by selling products in six major categories. We broke them down below:

Wines & Spirits: Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon, Ruinart, Krug, Veuve, Clicquot, Hennessy, Château d’Yquem, Glenmorangie, Clos des Lambrays.

Fashion & Leather goods: Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Celine, Loewe, Kenzo, Givenchy, Fendi, Emilio Pucci, Marc Jacobs, Berluti, Loro Piana, RIMOWA and Patou.

Perfumes & Cosmetics: Christian Dior, Guerlain, Givenchy and Kenzo, : Benefit, Fresh, Acqua di Parma, Perfumes Loewe, Make Up For Ever, Maison Francis Kurkdjian, Fenty Beauty by Rihanna, KVD Vegan Beauty and Officine Universelle Buly.

Watch & Jewelry: Tiffany, Bvlgari, Chaumet, Fred, TAG Heuer, Hublot, Zenith and Repossi.

Selective retailing: Sephora (beauty retailer), Le Bon Marché (Paris department store), DFS (travel retailer).

Other activities:

Groupe Les Echos (cultural news publications: ; Royal Van Lent), Cheval Blanc, Belmond (hotels).

Because LVMH is such a massive luxury group with so many moving parts, it makes sense to take a step back and look at each business segment individually. Not by diving into the financials, but by getting a big-picture view of the “how,” “what,” and “why” for each one.

2.2 - LVMH business segments

Fashion & leather goods segment

This is LVMH’s biggest and most profitable division. It often brings in over half of the company’s total revenue and an even larger share of its profit, with margins that are way above the other segments. Checking fashion & leather goods margins and growth is a reliable signal of how LVMH as a whole is doing.

Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior are the leading brands here. Their global appeal and iconic status give them major pricing power. What really makes these brands tick is their ability to create and remain desirable. That comes from carefully managed scarcity (real or perceived), heritage storytelling, premium quality, and positioning that goes way beyond typical advertising. That’s why these brands can charge deluxe prices and even have waitlists for some of their products.

Their desirability fuels strong pricing power, which translates into high gross and operating margins (>40% EBIT margins). What makes this “desirability engine” so hard for competitors to copy is that it’s been built over decades, creating a feedback loop: high demand → high profits → reinvestment in the brand → even higher demand. There’s also growth potential in newer brands like Fendi, Celine, and Loewe, which are gaining momentum within the portfolio.

Wines & spirits segment

This segment has been a very slower growing segment, and actually has been declining since ‘22. Operating margins (EBIT) range between 20-30%, particularly from cognac and premium champagnes. The performance is influenced by factors such as harvest quality (for wines) and global demand trends. Data on sales volumes and revenue from champagne (e.g., Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon) and cognac (Hennessy) often show a distinction between volume growth and value growth, with the latter benefiting from premiumization.

The global trend towards premiumization, where consumers opt for more expensive, high-quality products, is a potential growth driver. Asia, particularly China, has historically been a strong market for Hennessy cognac. The recovery of tourism and festive occasions also fuels champagne demand, as these beverages are often linked to celebrations and luxury experiences.

A potential reason for declining wine and spirits sales could be shifting consumer preferences towards healthier lifestyles, leading to reduced alcohol consumption, particularly in younger demographics. Additionally, economic downturns or geopolitical instability tend to reduce luxury spending, impacting demand even more.

Watches & jewelry

This segment attracts a wide range of consumers, with key brands like TAG Heuer, Bulgari, and Hublot leading the market. Although this segment accounts for roughly 13% of sales, and accounts for (just) 6.6% of operational profits (10Y-average). Operating margins range between 14-19% in this segment. The segment has gained significant importance, especially after the acquisition of Tiffany & Co.

Sales are driven by trends in luxury goods and the growing demand for high-end watches and jewelry, especially among affluent buyers in both developed and emerging markets.

I expect more growth in this segment in the coming decades, through innovation, and emerging markets, like India. They’re already tying technology (smartwatches, for example) with the craftsmanship of luxury watches.

Perfumes & cosmetics

This segment is a bit different from the others. It offers a taste of luxury through scent and cosmetics, without the steep price tags of watches or bags. Key brands include Christian Dior Parfums, Guerlain, and, more recently, Fenty Beauty by Rihanna. While not a high-growth segment, it still plays an important role in LVMH’s portfolio. It accounts for around 10% of revenue, down from 13% ten years ago, and only 3% of LVMH’s total operational profits. EBIT margins have also decreased, from 11% to just 8% in FY24.

That said, revenue has steadily grown from about €5.2 billion to €8.5 billion in FY24, reflecting a 7.2% CAGR. Iconic fragrances like Dior Sauvage and J'adore maintain a loyal customer base, supporting consistent growth and pricing power. Fenty Beauty has been a standout addition, making luxury beauty products more accessible and appealing to a younger, broader audience.

Although this segment is unlikely to be the fastest-growing or the top profit contributor in the long term, it remains vital in introducing new customers to the world of luxury. The future will depend on digital marketing and new sales channels, particularly as online beauty shopping continues to rise. Expanding in Asian markets, where there is strong demand for beauty and skincare, will be key. As platforms like Instagram and TikTok increasingly shape consumer decisions, LVMH’s focus on these digital channels will be important for sustaining growth in the perfumes and cosmetics sector.

Selective retailing

This segment includes Sephora, the travel retailer DFS, and other businesses like the luxury hotel group Belmond. Together, they contribute about 20% of total revenue but only 7% of operating profit, highlighting relatively slim margins, which tend to average between 7% and 10%.

Sephora stands out with its strong retail concept, broad brand portfolio, and loyal customer base, all key drivers of its success. DFS, on the other hand, is heavily tied to the recovery of international tourism, as it depends on travelers shopping for luxury goods in airports and travel hubs. Belmond caters to the growing appetite for experiential luxury, offering high-end travel experiences to wealthy consumers seeking more than just products. Looking ahead, the future of this segment hinges largely on Sephora’s global expansion. Despite already having over 2,700 stores across 35 countries, there's still significant room for growth. For example, Ulta Beauty, a Sephora competitor, has roughly 1,400 stores (30%+ market share) in the U.S. alone, while Sephora has just +/- 600 stores (20% market share) in the U.S. That means quite the growth potential, in the U.S. alone.

Each segment at LVMH plays a distinct role in the group's broader ecosystem. Understanding how each part contributes, and where the growth levers lie, gives you a clearer lens through which to view LVMH.

Chapter 3 - Sector & Industry

3.1 - The luxury market

The global luxury goods market reached approximately €363 billion in 2024, marking a 2% decline from the previous year. This contraction was influenced by factors such as consumer uncertainty, price increases, and a reduction in the number of affluent consumers. Despite this, the broader luxury sector, encompassing experiences and services, remained relatively stable, with global luxury spending projected to be around €1.5 trillion in 2024.

Looking ahead, the market is expected to experience modest growth. Projections indicate an annual increase of 1% to 3% from 2024 to 2027, with emerging markets in Latin America, India, Southeast Asia, and Africa anticipated to contribute significantly to this growth.

The core characteristics of luxury brands are:

Aesthetic appeal and quality: Luxury brands focus on creating visually stunning and high-quality products. This combination attracts high-end and passionate customers seeking beauty and superior craftsmanship.

Consumer as ambassador: Satisfied customers naturally promote luxury brands, acting as ambassadors who showcase their luxurious possessions within their social circles, thereby enhancing brand prestige.

Autonomy and authenticity: Luxury brands maintain their unique identity by making independent choices, staying true to their vision and values, which further strengthens their authenticity and appeal.

Exclusivity and scarcity: Luxury brands stand out by creating exclusivity and scarcity through limited production, unique products, and controlled distribution channels. This rarity boosts desirability and perceived value, appealing to consumers seeking status and individuality. The exclusivity is maintained through invitation-only events and personalized services to uphold the brand's elite image and allure.

You can categorize the luxury consumer into various segments. Understanding this global luxury consumer is crucial, as they are distinctly different from consumers in other sectors and industries. When we look at consumer preferences and behaviors, it becomes clear that large groups of consumers share common traits, regardless of their location on the planet. Consumers undergo a dynamic evolution in their purchasing mindset, advancing through a series of recognizable stages. (See next page).

Table 1 | Luxury consumer segmentation | LVMH 10k FY2024

Category | Brand Selective | Prestige Driven | Image Conscious | Quality Focused | Purpose oriented |

Motivation | Preference for global brands | Focus on social standing | Influenced by trends and belonging | Driven by personal well-being and beliefs | Value-based consumers |

Profile | Luxury newcomers | Status seekers | Community-driven | Luxury investors | New-age luxury pioneers |

Values | Emphasis on brand reputation | Prioritize visible luxury | Value life quality | Appreciate refinement | Focus on broader societal impact |

Reasoning | Limited understanding of brand depth | Buys luxury products to display status | Shares experiences on social media | Appreciate brand heritage, fabric, and craftsmanship | Chooses companies that are sustainable and inclusive |

Age | Predominantly 45+ | Mostly 25–35 | Mostly 25–35 | Predominantly 45+ | Mostly 18–24 |

Something I didn’t talk about in the Kering or Richemont report, is the word masstige. Which applies to LVMH like no other luxury company.

It's a blend of "mass" and "prestige," and it refers to products that offer a sense of luxury and prestige but are priced and marketed in a way that appeals to a broader, more mass-market audience. Masstige products typically maintain a premium image while being more accessible in terms of price and distribution, allowing them to sell in larger quantities compared to exclusive luxury goods. It's a strategy used by brands to offer a taste of luxury without the full exclusivity and high price tag, appealing to consumers who want to feel part of the luxury experience but at a more affordable level. The branding of masstige products often mimics the aesthetics of high-end luxury. Think of fragrances or cosmetics. Masstige brands are often available through department stores, drugstores, or supermarkets, making them widely accessible. Luxury brands, on the other hand, tend to sell through exclusive boutiques or limited channels.

The ability to purchase a masstige item at a local store or online platform allows consumers to experience a touch of luxury without the effort of visiting specialized stores or spending vast amounts of money.

But the masstige strategy, LVMH employs, carries both opportunities as it does risks.

Opportunities of masstige

LVMH’s masstige strategy offers the opportunity to reach a wider consumer base by making luxury more accessible, especially to younger, aspirational buyers. By offering more affordable luxury items like fragrances or collaborations, LVMH can attract consumers who might eventually upgrade to higher-end products. This approach also helps LVMH tap into emerging markets with growing middle-class populations, increasing volume sales and diversifying revenue streams. Essentially, masstige acts as a gateway for customers to eventually explore the full luxury offerings.

Risks of masstige

However, the masstige strategy carries the biggest risk of all; brand dilution. Offering lower-priced products can undermine the exclusivity of LVMH’s high-end image, making it less appealing to wealthy consumers who seek rarity. It the brand(s) dies, so does LVMH. Additionally, LVMH faces increased competition from both luxury brands and mass-market players imitating the luxury look at lower prices. There's also the challenge of maintaining consistent quality, as any inconsistency could hurt the overall brand perception, especially when consumers expect high standards across all products.

Masstige is a double-edged sword.

If you want to dive even deeper into the luxury market, we've created a comprehensive industry report that covers all aspects of the luxury sector. Check it out here.

Additionally, for those eager to learn more, there are several podcasts available that explore various facets of the luxury industry, from trends and consumer behavior to brand strategies and market shifts.

3.2 - Competitors

Comparing competitors in the luxury market is tricky. While they do compete for a slice of the pie, they do so in different ways. At the same time, each brand maintains its own unique market position. However, if we were to line up the biggest competitors, it would look something like this:

Kering

Hermès

Richemont

Chanel

Kering, with high-profile brands like Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent, holds a significant market share, while Richemont, with its luxury brands like Cartier and Montblanc, commands a strong presence as well. Chanel, an independent company, remains one of the top players in the industry.

Given that the market was valued at around €363 billion in 2024, LVMH holds approximately 23% of this market share based on total revenue.LVMH operates in almost all luxury segments, except for luxury cars. Historically, Kering with its flagship brand Gucci was considered the biggest competitor. However, due to recent challenges with Gucci, this gap is closing, and Hermès is now emerging as a stronger rival. That said, Kering still holds about 5% of the luxury market share.

Incredibly, Hermès is now worth more in market capitalization than LVMH (€257 billion vs. €247 billion), making it a formidable competitor. Additionally, I believe Hermès offers a level of luxury that is more exclusive than LVMH’s and focuses less on masstige. Hermès commands around 4% of the market share.

Richemont remains a direct competitor, especially to LVMH's brands like Tiffany and Bulgari, with a market share of about 5.5%. Finally, there's Chanel, which, although not publicly traded, is still a major player. According to Forbes, it was valued at nearly €20 billion in 2023, equating to more than 6% of the luxury market.

These competitors vary in strategy and positioning, but they all remain formidable players that LVMH has to keep an eye on.

Chapter 4 - Competitive advantages

LVMH’s competitive advantage lies in its ability to nurture and elevate its individual brands through the combined benefits of scale, resource allocation, and market presence. At its core, LVMH is a highly strategic holding company that leverages its infrastructure, advertising power, and financial resources to ensure each of its brands thrives in a competitive market. However, this advantage depends fundamentally on the brand power of each individual Maison (brand), and maintaining that power is crucial to the company’s long-term success.

Synergies

One of the primary competitive advantages of LVMH is its ability to offer operational synergies between brands while allowing each brand to retain its independence. The conglomerate benefits from its economies of scale, ensuring better locations for flagship stores, more effective advertising campaigns, and higher investment potential. It also helps attract and keep top creative and management talent, who value that independence. This structure makes LVMH more resilient, if one brand messes up, it doesn’t bring the whole group down. It also makes LVMH appealing to founders who want to sell their company but still see it continuing to grow. The challenge here is making sure brands in the same category don’t step on each other’s toes, which takes careful positioning and differentiation. This support infrastructure allows LVMH’s brands to focus on innovation and craftsmanship, leaving the corporate heavy-lifting (such as real estate and marketing) to the holding company. As a result, brands can perform better in terms of profitability, storytelling, improving craftsmanship and market presence compared to standalone brands that may not have the same resources.

LVMH’s ability to secure premium retail locations around the world, particularly in high-demand cities like Paris, New York, and Shanghai, also gives its brands a significant advantage. As you probably know by now, in luxury it’s not about the product itself or even the utility, it’s about the experience and exclusivity. Securing the best locations enhances that experience, creating a sense of prestige for the consumer.

In terms of advertising, LVMH's ability to consolidate marketing efforts across its brands allows it to reduce costs while maintaining a high level of brand exposure. This not only lowers the cost of customer acquisition but also builds a unified image of luxury that benefits all LVMH brands.

Brand power

Ultimately, LVMH’s moat is built on brand power. LVMH’s portfolio is made up of brands that carry tremendous prestige and heritage. Brands that have been cultivated over decades. This legacy, along with their commitment to quality, craftsmanship, and exclusivity, makes these brands highly desirable to luxury consumers. However, brand power is a fragile moat. If a brand loses its unique appeal, as seen with Gucci recently, its pricing power and ability to command luxury prices diminish. Once a brand loses its prestige and luxury status, it becomes exceedingly difficult to regain the same level of market position or pricing power. Gucci, once a leader in luxury fashion, is now struggling with an identity crisis, leading to declining sales and a loss of market share, even though Kering (Gucci’s parent company) continues to push for a revival.

In the luxury market, having a moat is paramount. Brand equity is the strongest moat in this industry, and it’s what separates successful luxury companies from those that fail. The ability to command luxurious prices for products based on heritage, quality, and exclusivity is something that only a few brands can achieve. LVMH has mastered this by acquiring brands with long histories of craftsmanship and cultivating them in a way that they continue to be seen as aspirational and exclusive.

Without a strong moat, companies in the luxury sector tend to fail or struggle. Many luxury brands that have collapsed, or lost relevance (think Burberry pre-2006, Abercrombie & Fitch, Pierre Cardin, Escada, Coach, did so because they failed to maintain their branding power, whether by over-expansion, lowering product quality, or failing to adapt to changing consumer preferences. The “mass luxury” approach that dilutes the exclusivity of certain brands, or the failure to innovate while maintaining quality, often leads to the downfall of these companies.

In my opinion, LVMH’s moat is stronger than Kering or Richemont. While competitors like Kering (with Gucci) and Richemont (with Cartier and Montblanc) have strong brands, they don’t have the same diversified portfolio that LVMH enjoys. LVMH can weather shifts in consumer preferences across different product categories, from fashion to spirits to cosmetics, which reduces its overall risk. Additionally, leather goods, such as bags, tend to evolve at a much slower pace compared to fashion items like clothing.

Now, Hermès, LVMH’s biggest competitor, has a narrower focus, which has allowed it to maintain an even more exclusive and luxury image. However, Hermès’ smaller portfolio means that its brand power is more concentrated. LVMH benefits from spreading risk across multiple brands and sectors. Additionally, Hermès has a higher brand equity, but LVMH’s ability to invest heavily in new ventures and elevate its brands through acquisition gives it a unique advantage in my opinion. The sustainability of LVMH’s moat depends largely on the continued strength of its individual brands. The brand power of Louis Vuitton, Dior, and other Maisons is crucial for LVMH’s long-term dominance in the luxury market. As long as these brands continue to deliver on their promise of exclusivity, quality, and heritage, LVMH’s competitive edge will remain strong. However, the moment any of these brands lose their appeal, the entire structure is at risk. Especially the most important brands, like LV, Tiffany or Dior.

Chapter 5 - Management

I believe that for a company like LVMH to be a good investment, it ultimately comes down to exceptional management and execution. Nothing more, nothing less. That’s why, in this chapter, we’ll take a deeper dive than usual.

As I’ve mentioned in previous interviews, I’m convinced that management holds more weight than any competitive advantage in the long run. And when it comes to luxury companies, they’re uniquely positioned to play the game for the extremely long haul.

Usually, the management team is most important, and they are. However, in the case of LVMH, I’d argue the board of directors is more important here. We’ll get to that in a second.

Chairman and CEO - Bernard Arnault

Born on March 5, 1949, in Roubaix, France, he studied at the prestigious École Polytechnique before starting his career as an engineer. He is married and has five children.

He became Chairman of the construction company Ferret-Savinel in 1978 and later turned around the Financière Agache holding company, setting the foundation for LVMH’s creation. In 1989, Arnault became the majority shareholder of LVMH. He also serves as President of Groupe Arnault, his family holding company.

Group Managing Director – Antonio Belloni

Stéphane Bianchi, born on January 10, 1965, in France, is the Group Managing Director of LVMH. He began his career as a consultant at Arthur Andersen before joining the Yves Rocher Group, where he became CEO at 33. In 2018, Bianchi joined LVMH as CEO of TAG Heuer and the Watchmaking Division, later overseeing major brands like Bulgari, Tiffany, and Zenith.

In 2024, he was appointed Group Managing Director, responsible for the strategic and operational management of LVMH's Maisons, as well as overseeing the Regional Presidents and driving the company’s Digital and Data Transformation. Bianchi is also Chairman of the Executive Committee.

CEO of Christian Dior Couture – Delphine Arnault

Delphine Arnault, born on April 4, 1975, began her career as a consultant at McKinsey before moving to John Galliano’s company in 2000, where she gained hands-on experience in the fashion industry. In 2001, she joined Christian Dior Couture and served as Deputy Managing Director from 2008 to 2013.

In 2013, Delphine was appointed Executive Vice President of Louis Vuitton, overseeing all product-related activities. Since February 1, 2023, she has been the Chairman and CEO of Christian Dior Couture. Delphine is also a member of the LVMH Board of Directors and the Executive Committee.

Head of development and acquisitions – Nicolas Bazire

Nicolas Bazire, born on July 13, 1957, is the Head of Development and Acquisitions at LVMH. Since joining in 1999, Bazire has been instrumental in identifying and securing high-potential brands that align with LVMH's vision for growth and market dominance.

In 1999, he was appointed Managing Director of Groupe Arnault, where he became a key figure in LVMH’s development.

Louis Vuitton – Pietro Beccari

As the CEO of Louis Vuitton, Pietro Beccari is responsible for the direction of the world’s most iconic luxury brand. Beccari oversees the development and operations of Louis Vuitton, driving its strategy and maintaining its position as LVMH's most important revenue generator.

Under his leadership, the brand has successfully expanded its global footprint. Beccari’s known for his deep understanding of brand heritage, combined with his ability to innovate, ensured that Louis Vuitton remains a symbol of exclusivity and craftsmanship.

CFO – Cécile Cabanis

Cécile Cabanis, born on December 13th, 1971, is the CFO of LVMH. Cécile brings extensive experience in key finance roles, particularly in mergers and acquisitions and financial communications. She began her career at L'Oréal in South Africa in 1995. Cécile also spent 17 years at Danone, where she was appointed CFO in 2015. In June 2024, Cécile became Deputy CFO at LVMH, preparing for a future succession alongside Jean-Jacques Guiony, the then-current CFO. On February 1, 2025, she officially took over as CFO of LVMH.

The Arnault family

Like I said before, the board of directors might be just as, if not more important (read, influential) to LVMH. They control the direction and strategy.

Bernard Arnault has five children, from oldest to youngest, each with notable roles within LVMH and Christian Dior. As of May 2025, their roles are as follows:

Jean Arnault (1998): Director of Louis Vuitton Watches.

Frédéric Arnault (1995): CEO of Loro Piana (since May. 2025)

Alexandre Arnault (1992): (Deputy) CEO of LVMH Wines & Spirits

Antoine Arnault (1977): CEO of the family holding company Christian Dior.

Delphine Arnault (1975): CEO of Christian Dior Couture.

There is a culture where you must work hard and prove yourself. Nothing is given for free. It must be earned. All the children move throughout the company, transitioning from role to role, to gain experience. Ultimately, one of the five children will (or rather, ‘likely’) take over from Bernard.

Shareholder structure

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE is predominantly controlled by Bernard Arnault and his family. Through the Arnault Family Group, they hold approximately 50% of the company's shares and 64% of the voting rights, ensuring plenty of influence over strategic decisions. The Arnault family runs the ship.

An important detail, which I will elaborate on further towards the end, is the Christian Dior SE holding company. This publicly listed holding owns nearly 42% of LVMH's shares and almost 57% of its voting rights.

5.1 - Incentives & Skin in the game

LVMH's incentive structure revolves heavily around bonus share plans and employee share ownership schemes. In 2024, the company granted nearly 291,000 bonus shares across several plans, with most having multi-year vesting periods. Around 93% of the 2024 grants were performance-linked. It’s unclear what performance benchmark they use. While Hermès ties incentives closely to cash flow and organic growth metrics, LVMH leans on share vesting linked to tenure and performance.

Skin in the game is nothing to worry about, with the Arnault family owning roughly 50% of the company, worth around €120 billion. While I don’t believe the family really works for money anymore, because they are set for life, for those interested, here are some highlights:

Bernard Arnault (CEO) earned a base salary of (just) €1 million and variable compensation of €7 million. He owns roughly 0.2% directly, worth €500 million. His family members are worth between €50-€200 million and earn combined compensations between €1 and €3 million annually. Nothing to worry about here.

Chapter 6 - Financial analysis

6.1 - Key numbers

Revenue grew from €35.6 billion in FY15 to €86.6 billion in FY24. This translates into a 10.4% CAGR. During the same period, the cost of goods sold grew from €12.5 billion to €27.9 billion, or a 9.1% CAGR. So revenue grew a bit faster than COGS, meaning they were able to increase revenue, without a proportional increase in production or operational expenses.

Over the same time, operating income increased from €6.6 billion to €19.6 billion, or a 12.9% CAGR. Operating margins increased from 18.5% to 23%, and reached highs of 26.7% during FY21.

LVMH's free cash flow (FCF) conversion has generally been strong and consistent, averaging above 100% over the last decade. Even in weaker years like 2023 (76.4%), the business still converted a significant portion of earnings into cash.

6.2 - Capital allocation

Table 2 | LVMH Capital allocation | Finchat & LVMH ‘24 10K

Figures in billions of € and rounded | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

Free cash flow | €8.9 | €16 | €13.4 | €11.6 | €14.2 |

Dividends | €2.3 | €3.5 | €6 | €6.3 | €6.5 |

Share buyback | €0.3 | €0.7 | €1.6 | €1.4 | €1.3 |

Debt repayment | €7.3 | €8.9 | €6.6 | €6.8 | €6.6 |

Acquisitions | €0.5 | €13.2 | €0.8 | €0.7 | €0.4 |

FCF left (in €) | -€1.5 | -€10.3 | -€1.6 | -€3.6 | -€0.6 |

LVMH’s capital allocation implies a focus on growth, shareholder returns, and brand expansion, all of which have been funded by a combination of debt and the company’s cash reserves. Over 40% of free cash flow (FCF) is allocated to dividends, and frankly, given the current valuation and market uncertainty, I wouldn’t mind seeing them lower the dividend and increase the share buyback program instead. This could be a more effective use of capital for shareholders. The key question is whether this approach is sustainable in the long term. Only time will tell.

6.3 - ROIC

ROIC measures how effectively the company generates profit from its invested capital, which includes equity and debt used to finance the business. Pretty useful for a company like LVMH. LVMH operates in a capital-intensive luxury market, where value comes from long-term investments in brand building, retail expansion, and acquisitions, like the purchase of Tiffany & Co.

ROIC shows how well these investments are generating returns compared to the capital LVMH has used.

However, goodwill from acquisitions can lower ROIC, as it's part of the capital but doesn’t directly add to profits. This makes LVMH’s ROIC appear lower than companies like Hermès, which grows more through internal development and doesn’t rely as much on acquisitions. Despite this, LVMH’s strong ROIC still reflects its ability to generate significant returns, thanks to its diverse portfolio of luxury brands and strong global presence.

I’ve also decided to calculate ROIIC (Return on Incremental Invested Capital) to better understand how efficiently LVMH is using its capital in its core luxury operations. By comparing LVMH’s ROIIC with that of Kering, Hermès, and Richemont, we can assess how each company is generating returns from its luxury brands and managing capital. This comparison is valuable because, even though these companies operate in the same industry, they follow different strategies when it comes to acquisitions, capital management, and organic growth.

Table 3 | ROIC by company | Finchat

LVMH | Hermes | Richemont | Kering | |

ROIIC | 4.8% | 18.5% | 2.3% | 1.9% |

Hermès' ROIIC is exceptionally high, reflecting its outstanding efficiency in generating returns on new investments. In comparison, LVMH’s ROIIC is moderate, which is understandable given its vast size and diverse portfolio, but there is still room for improvement. Meanwhile, the ROIIC for Richemont and Kering is quite low, indicating that both companies are struggling to generate strong returns from their recent investments. All things considered, LVMH is doing fairly well, especially given its size, but it is still not as good as Hermès.

6.4 - Debt analysis

LVMH is a company with extensive experience in managing capital and debt. Fortunately, this is crucial because LVMH’s success will depend on managing its Maisons, making smart use of debt, and executing acquisitions.

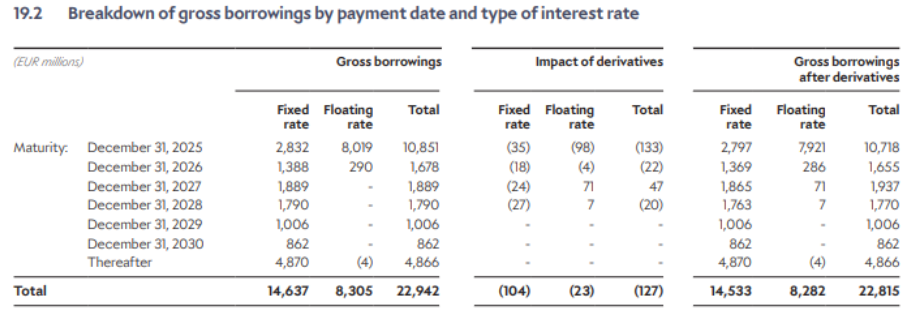

In FY24, LVMH had €10.7 billion in short-term debt and €12.1 billion in long-term debt. Additionally, LVMH holds significant long-term leases due to its many stores, offices, and ateliers. These leases amount to €14.9 billion. When you subtract this from the net cash position of €13.6 billion, it leaves roughly -€27 billion. With the current operational cash flow of €18.9 billion, it would take roughly 1.5 years to cover this. Despite the large figures, I don’t see the debt as a major risk for LVMH at the moment. They’ve demonstrated in the past that they can manage it effectively.

One of LVMH’s strengths and advantages is that their size and experience are reflected in their moat. In 2024, LVMH received an Aa3 rating from Moody’s, and an AA- from S&P, allowing them to borrow debt at a lower interest rate. Currently, there are several bonds with varying interest rates. In FY2025 (this year), LVMH will need to repay about €10.9 billion. I foresee little trouble with this in the coming years.

6.6 - KPI’s

The key performance indicators (KPIs) I specifically track for LVMH are:

Revenue growth across all divisions, with a particular focus on fashion & leather goods, as these currently represent the largest source of profit.

Organic growth for each division and for LVMH as a whole.

I also focus on EBIT growth rather than net income or free cash flow growth because EBIT provides a clearer picture of the company’s operational performance, without the impact of interest or taxes. I also closely monitor the EBIT margin.

Finally, I see significant potential in selective retailing and watches & jewelry. So I pay close attention to EBIT margins and the overall trend in these divisions, as I believe they hold room for future growth.

Chapter 7 - Risk analysis

7.1 - Risks

Macro-economic risks

The luxury sector is inherently cyclical, as spending on luxury goods is discretionary and can significantly decline during economic recessions when people have less to spend. Inflation and rising interest rates also impact consumers' purchasing power and sentiment. Aspirational luxury consumers, in particular, may scale back their spending during tough economic times. However, LVMH's broad portfolio allows it to serve both aspirational consumers and high-net-worth individuals, which presents both an advantage and a risk. LVMH may be more resilient during recessions than many assume, as long as its top brands continue to maintain their desirability.

Geopolitical tensions

Trade tensions (e.g., between the US and China), international conflicts, disruptions in tourism due to political instability or pandemics, and regulatory changes in key markets can have a significant impact. The evolving policy in China, particularly the “common prosperity” agenda, is closely watched by the luxury sector. LVMH’s significant dependence on Chinese consumers, both in mainland China and through tourism, makes it vulnerable to shifts in government policy or consumer sentiment.

Brand reputation damage

The value of LVMH is intrinsically linked to the reputation of its brands. Incidents like the sale of counterfeit products, ethical missteps (e.g., animal welfare or labor conditions in the supply chain), or a loss of creative vision at a major maison can seriously harm brand value and consumer trust. Maintaining the integrity of its high-end brands is essential to LVMH’s long-term success, and any reputational damage will lead to a sharp decline in demand.

Supply chain disruptions

Problems with sourcing key materials (like high-quality leather, gemstones, or grapes for wine), production limitations, or logistical disruptions could delay production and delivery, driving up costs. Because LVMH products are known for their high craftsmanship, any supply chain issues could affect product availability, quality, and delivery times. While price increases could help offset a decline in volume, this strategy would only be effective if the supply chain disruptions aren’t too severe.

7.2 - Opportunities

The to-go holding company

This might be a bit unconventional, but as the largest luxury holding company with an exceptional portfolio of brands, heritage, and experiences. LVMH has a major advantage in becoming the go-to destination for newer luxury companies looking to sell or merge. It stands as an ideal partner for other luxury brands seeking growth while maintaining their uniqueness and heritage. In the watch and jewelry space, Richemont is the only real alternative. In fashion, Kering is a competitor, but it’s currently facing significant struggles, which weakens its position. I don’t foresee Hermès pursuing acquisitions, as this doesn’t align with their strategy and could harm their heritage and style. As the luxury market continues to consolidate, I believe LVMH is well-positioned to benefit from these trends over the long term.

Digitalization and e-commerce

While LVMH is exploring Web3 technologies and NFTs (which I believe will offer limited benefits), I do think technology can strongly enhance the brand's value proposition. Imagine being able to witness the entire process of a craftsmanship item being made, or virtually walking through an atelier in the Metaverse, this would offer an immersive experience that elevates storytelling and deepens the consumer connection to the brand.

The focus of technology, in my view, should be on enhancing experiences and reinforcing the heritage of luxury brands. For instance, integrating technology into products like smartwatches or leather bags with hidden tech, think of using fingerprint identification to open a bag, could blend tradition with innovation. There's also potential for AI to streamline operations, reduce unnecessary headcount, and improve efficiency, all while enhancing customer engagement. There’s a lot to explore here, and the future of how technology can improve luxury brand experiences is full of exciting possibilities.

Pricing power

LVMH’s pricing strategy is built on the idea that true luxury items become more desirable as their prices rise. The paradox of luxury is that higher prices often increase exclusivity, which in turn makes the products even more sought after. As long as LVMH can maintain its position at the top of the luxury market and avoid sliding into the premium segment, it should be able to consistently raise prices above inflation, preserving or even growing its margins.

Chapter 8 - Valuation

This is where things get interesting, but also complicated. How do you value a company like LVMH? Of course, you can value it based on multiples or a scenario analysis, but this will likely give a skewed picture. LVMH is the shell, but the brands underneath it are the gunpowder. They provide the drive, power, and long-term profits.

That’s why I’ve decided to value LVMH based on sum-of-the-parts. This is a very personal approach, and my assumptions will likely differ from others' views. Therefore, you’ll need to critically assess the valuation yourself, but this is my most realistic view and set of assumptions. It’s up to you to decide whether you want to be more conservative or aggressive with your assumptions or valuation method.

8.1 - Ratios

I think there are only two useful valuation metrics for LVMH, especially comparing them to competitors: EV/EBIT and P/E.

EV/EBIT

I chose EV/EBIT because it provides a clear view of how the market values LVMH’s operational earnings, excluding interest and taxes. This metric is particularly useful for companies like LVMH, which have a diverse portfolio of brands. It helps assess operational efficiency and compares the enterprise value, reflecting both debt and equity, relative to the company’s profits. This is especially important in the luxury sector, where high operating profits are common and a company’s valuation is tied to its operational performance rather than just profit.

Believe it or not, but LVMH has never been cheaper, based on EV/EBIT. Hermès always looks expensive, and Richemont seems pretty fairly valued based on (just) EV/EBIT.

P/E

The P/E ratio provides a simple way to compare how the market values LVMH’s earnings relative to its competitors. Since LVMH operates in the luxury sector with relatively stable earnings, the P/E ratio gives an easy benchmark for assessing whether the company is undervalued or overvalued based on its profits. It also helps gauge the market sentiment toward each company.

Hermès also looks extremely expensive (55x), not only compared to the competition, but also compared to the past. LVMH, Kering and Richemont all trade around 25 times earnings. Not cheap, however, it’s an inflated number. The P/E ratio of 25 looks high compared to EV/EBIT because P/E includes the impact of taxes and interest, while EV/EBIT focuses purely on operating performance, excluding financing costs. Especially since LVMH has a large scale and has significant interest payments and tax liabilities.

8.2 - Sum of the parts

Alright, now we’ve reached the fun part, where we get to play around with our assumptions and arrive at a reasonable estimate of LVMH’s true value. Ideally, I’d love to value the key brands individually, but since LVMH doesn’t report results at the brand level, we’ll value it by business group instead. It’s a bit less precise, but fortunately, valuation isn’t an exact science, it’s more about working within a range of outcomes, estimates, and assumptions.

Wines & Spirits

With high brand equity, think Hennessy and Moët, resilient margins, and strong cash flows, this segment resembles a luxury version of consumer staples. Comparable companies like Pernod Ricard and Diageo typically trade at low-to-mid teen multiples. While growth has been tapering off since 2023, the business still boasts robust 23% operating margins, underscoring its underlying strength.

Fashion & Leather Goods

This is LVMH’s crown jewel. Ultra-high margins, best-in-class brands (Louis Vuitton, Dior), and pricing power unmatched in the industry. Structural global demand and scarcity value in luxury fashion justify a premium. High teens to low 20s is conservative relative to market admiration for these assets. Has had a rough couple of years, but still declined just 3% in tough economic times, and grew 46% in ‘21. Operating margins of 37% command a higher multiple.

Perfumes & Cosmetics

While this segment faces lower margins and stiffer competition compared to Fashion, it still benefits from strong brands like Dior Beauty and Guerlain. The global beauty market is growing, particularly in Asia, but it comes with higher commoditization risk. It’s comparable to players like Estée Lauder or Coty, which typically trade in the high single to low double-digit multiples. Despite steady growth, the lower operating margins justify a more conservative multiple.

Watches & Jewelry

Brands like Tiffany and Bulgari carry undeniable luxury appeal, but their margins don’t quite reach the exceptional levels seen in Fashion. Growth is steady rather than explosive, and the category tends to be more cyclical and fragmented. Comparable players like Richemont and Swatch typically trade in the low teens. Still, the segment delivers solid operating margins of nearly 15% and has shown consistent growth. There's meaningful room for expansion, supported by strong brand equity. The acquisition of Tiffany in particular has elevated the segment’s profile and justifies a higher multiple than in the past.

Selective Retailing

This is the most mixed segment. Sephora is a standout performer, but its strength is offset by lower-margin, retail-heavy businesses like DFS and Le Bon Marché, which drag down the overall profile. Traditional retail typically commands lower multiples unless it's highly scalable or digitally driven. While Sephora on its own could justify a significantly higher valuation, the blended nature of the segment brings it down. That said, Sephora’s strong growth trajectory does warrant a modest uplift in the overall multiple compared to what this segment would merit without it.

Others

This is kind of a black box. It generated €504 million in revenue, but posted a loss of €617 million, so it’s not profitable and clearly a drag on group earnings. I used an exit multiple of 0, just to be conservative and forget about this group.

Conclusion on sum of the parts

If you ask me, these are very realistic assumptions, perhaps even a bit on the conservative side. Taking all of this into account, and assuming you find the assumptions credible, LVMH is trading at a 30% discount to its intrinsic value based on the current share price (€487).

I’ve got one final gift (see 8.3) and insight for you before we head to the conclusion.

If LVMH converges to its intrinsic value in 5 years, you're looking at:

~7% IRR buying LVMH directly.

~12% IRR buying Christian Dior SE instead.

8.3. Christian Dior SE

As we saw earlier, based on our assumptions, LVMH appears to be trading at around a 30% discount when you value its underlying brands and business groups individually. But believe it or not, there’s a way to buy into LVMH at an even steeper discount, simply by purchasing a different stock.

In the section on management and incentives, we mentioned that Christian Dior SE is the holding company controlled by the Arnault family. By investing in Christian Dior SE, you're essentially buying LVMH, but at a discount. As of May 13, 2025, that holding discount is around 18%. Add that to the estimated 30% undervaluation of LVMH itself, and you're effectively buying LVMH at a significantly deeper discount through Christian Dior. Of course, there's no guarantee this discount will ever close. As we've discussed before, holding discounts can persist for years, or even widen further during periods of uncertainty or market stress. Still, when you're buying the same underlying business for less, the question becomes: why pay more?

Historically, there have been moments when the discount narrowed, resulting in extra upside for Dior shareholders. Over the past 15 years, LVMH has delivered a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.6%, while Christian Dior has slightly outperformed with a 15.3% CAGR. That may sound like a minor difference, but over time it adds up: a $10,000 investment would have grown to $75,000 in LVMH, versus $82,000 in Christian Dior. Not bad for simply choosing a different ticker.

That said, there are valid counterarguments and risks. By buying Dior, you’re indirectly investing in LVMH, you don’t own LVMH shares outright, but rather shares in a holding company that owns LVMH. That means no direct voting rights, and no direct access to LVMH’s dividends, which first pass through Dior.

And while this isn't a major issue for long-term retail investors, it's worth noting that Dior shares are much less liquid than LVMH. Daily trading volumes are lower, which can make it harder to enter or exit a position quickly without affecting the price.

Chapter 9 - Conclusion

After analyzing the fundamentals, valuation, and management of LVMH, I see no reason to change course. I’ll continue holding my position, it remains a cornerstone of my portfolio for the very long term. The company has proven time and again that it can adapt, execute, and outperform through cycles. And most importantly, I fully trust the management team and their deep expertise in navigating both legacy and innovation within the luxury world.

I hold Christian Dior SE, the holding company that owns ~42% of LVMH. Why? Simple: the holding discount. As of now, that discount sits around 18%, which, when combined with LVMH’s estimated intrinsic undervaluation, gives me exposure to the same company at an even more attractive price. If that discount were to widen, I would consider adding more to Dior, although I won’t let it grow beyond 20% of my portfolio.

Of course, I’m not blind to the downsides. Dior gives you indirect exposure, and the shares are less liquid than LVMH. But as a long-term investor, that’s a trade-off I’m happy to make for the added margin of safety.

That said, I’ll continue to monitor whether LVMH stays on course, not chasing short-term gains, but focusing on brand equity, innovation, capital discipline, and long-term KPIs. Execution must remain consistent. Luxury is about perception and positioning, and any slip-ups could erode the moat quickly.

While I personally admire Hermès and would love to own it, at current valuations, I believe LVMH offers more attractive long-term returns over the next decade, even more so than Hermès or Ferrari. With its brand portfolio, pricing power, and diversification, LVMH is arguably one of the best risk-adjusted bets in the luxury industry.

I believe the opportunities still far outweigh the risks. And until that changes, I’ll remain both a patient holder, and a quiet accumulator when the market gives me a reason to be.

Onto the next one.